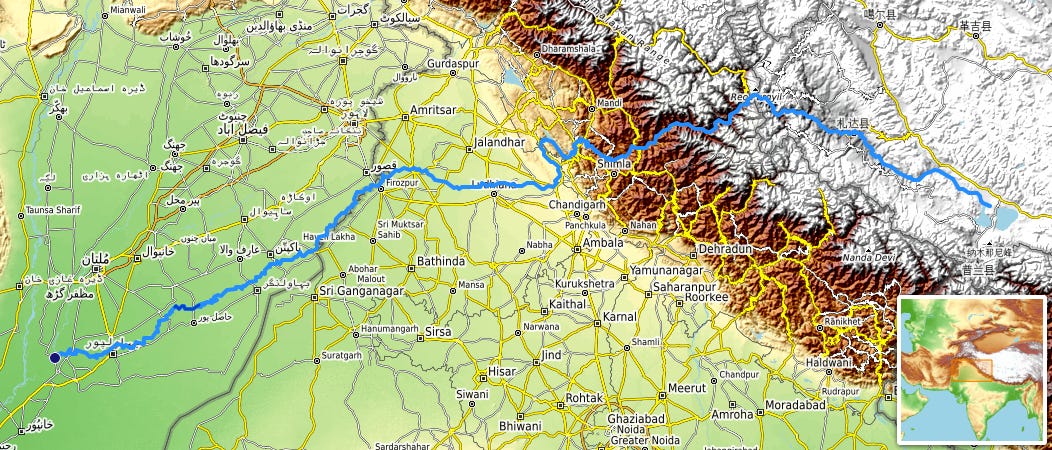

We usually imagine rivers descending down from the cold northern mountains and then flowing towards the seas in the south. Satluj rather flows from east to west. It divides Punjab into a North Punjab and South Punjab. My home is on one of its northern banks.

In the last thirty years, I have grown up here, left, come back and left this place many times. Yet, I’ve had a transactional relationship with these lands at best. I added an additional floor and a new face to the house that my parents made in the 80s. I insisted the face to look like one of those wooden victorian houses in Chicago which have large bay windows, porches and little balconies with balustrades. Instead of a large sprawling veranda to shade from the intense summer sun I got a cornice on the first floor and, despite trying my best, couldn’t get the mason to add corbels to give it a Scottish baronial look. Result: all the paint and varnish on the bay windows has evaporated in just one season, two of the massive windows broke their panes in a storm; and the drawing room and a bed room on the first floor are inhabitable in summer afternoons with the sun sitting right on your shoulders. The light is great in winters, it looks stunning in photographs— you just have to get cooked for some months every year.

Was I chasing some form of aesthetic superiority among all the other houses in the area? May be. Houses are very much a class symbol here and people do go to great extremes to certify their foreign remittances back home by putting aeroplanes and tractors on their roofs or by building as big as architecturally possible. I find that crass and maybe I turned to detail but to achieve the same goal as everyone else? May be. But I think there was something more fundamental going on in my mind at the time: I never visioned myself growing old here, living here through all the seasons. I didn’t see my parents living here for very long either. And the resulting home, though made with a lot of love and care from all of its members, ended up adding to the rampant encroaching, extracting, blocking and misfitting the earth it stands on rather than enriching the community.

***

I write about this because I’ve been continuously thinking about my relationship with these lands, the lands on the banks of river Satluj — where I’m the fourth generation to live after coming here from Sialkot post the 1947 partition of Punjab. Another example: Rahon, the town I live in, is the first big settlement immediately north of Satluj in this wider area. But between the settlement, Rahon, and the river, Satluj, there is an endless maze of canals, feeders and sub-canals that irrigate the lands in hundreds of villages and an equally big network of country roads that take you to all these villages. As a man of these lands, I feel, it is my responsibility to know all of these paths of the water and the foot by heart. It is my responsibility to know where Satluj was and where did it move and when did it move, how the lowlands and uplands and the riverines were created, which parts have loam and clay soil and where it turns sandy. I should know the paths of the nairhi and kail naddi riverines, the marshes, which were destroyed, the forest of the dhak trees, the names and the residents of its villages, havelis and trees. I should know when the winds are easterly and bring rain and what’s the time when the northern star shines.

I lack on most of this local lived knowledge. But I’ve been trying to mend. I’ve never had a car and don’t really plan to own one but a friend loaned me a very old Toyota this summer and I’ve tried my best to get lost and find my ways through the country roads and to walk next to the canals and the river Satluj. Some of these roads have been incredibly beautiful like the one that goes from Saloh to Sehbajpur and then to Rahon by the slim water feeder.

***

The large systems of irrigation and fresh river waters mean that the lands are extremely fertile and it is easy to grow any thing here — from staple wheat to haas avocados. No wonder then most people around me who have stayed here farm. So, another part of trying to find my place of co-existence with these lands has been to understand the food that I eat and is grown around my home. I would like to quote a little Wendell Berry here

“We still (sometimes) remember that we cannot be free if our minds and voices are controlled by someone else. But we have neglected to understand that we cannot be free if our food and its sources are controlled by someone else. The condition of passive consumer of food is not a democratic condition. One reason to eat responsibly is to live free.”

Though increasingly hard now but almost all that we ate growing up was locally made. We had the drums of local wheat and corn, local dairy, local seasonal fruits and vegetables as the staple diet. But I have long understood that locally made doesn’t necessarily means that they produced in any form of harmony with these lands. I have attempted this summer to get to growing my own food and to catch up on the two decades of missed chances of acquiring practical farming skills. The apparent illusion of harmony and sustainability of the local farming practices has been precisely that — an illusion.

It is paddy season and I think the Punjab farmlands these days could be a cover image of extractive farming anywhere in the world. It requires a severely unsustainable amount of water which is pumped out of the ground, depleting the water tables. The excessive use of fertilisers means that the topsoil is anything but natural. The lands are laser levelled and have encroached upon all the natural trees and paths through these lands. I like the quiet and calm of the farms but the unease that comes with knowing that you are standing right at the epicentre of ecological destruction doesn’t really lets you read a book in peace, does it?

(In the first image you see Rahon atop the mound in the background. Isn’t it beautiful!)

I have taken small steps. My mother likes mangoes so I planted two mango trees. An uncle saw me plant and he planted twenty. So now we have twenty two mango trees. I’m clearing and preparing land for a vegetable garden. I have moved towards having a few acres that I could conserve, that I could take out from the extractive industrial farming cycle and grow fruits, flowers and local grains.

Obviously, being a true part of these lands doesn’t just means having a somewhat decent knowledge of the geography and knowing how to farm. Acknowledging my position as an upper caste man who has viewed these lands as the means of ownership over bodies and nature is an important part. Being a part of the community and helping my fellow residents is an important part. Mending my relationships with the people who have walked with me on these lands is an important part. Hopefully. One day. It is going to take time. Not that I have anywhere to rush anyways.